Montana

Managed by National Park Service

Established 1879

765 acres

Website: www.nps.gov/libi

Overview

You may not recall the 1876 battle at the Little Bighorn River in southern Montana, but most Americans (even children) recognize its label “Custer’s Last Stand.” For such a relatively minor skirmish in the bloody 1800s, it has an outsized legend that only grows with time. At this site more than 140 years ago, a large portion of the 7th U.S. Cavalry met their demise for tactical reasons still debated to this day. The blame is generally placed upon Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer who was believed to be jockeying for a presidential nomination in the 1876 election. Today this National Park Service (NPS) site is located on the Crow Indian Reservation in southern Montana, just off Interstate 90.

Know someone who loves exploring new National Monuments? Gift them our book Monumental America: Your Guide to All 138 National Monuments that is available for sale on Amazon.com.

Highlights

Museum, Custer National Cemetery, driving tour, Last Stand Hill, Indian Memorial

Must-Do Activity

On June 25, 1876, with only 600 soldiers, Custer attempted to defeat a temporary village composed of multiple tribes numbering over 7,000 individuals. Never before had so large an American Indian encampment been collected anywhere on the Great Plains. Renowned war chiefs Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, Two Moons, and many others have their words memorialized at the Indian Memorial, not built at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument until 2003 near the mass grave on Last Stand Hill. Be sure to come in late June for the opportunity to witness a historical reenactment of the famous battle, which is held on the Crow Indian Reservation adjacent to the 765-acre National Monument.

Best Trail

None

Instagram-worthy Photo

The Battle of the Little Bighorn Reenactment is a two-hour, fully narrated presentation explaining the significance of the Battle of the Greasy Grass (as the American Indians call it). The site of the reenactment is a ford where Lieutenant Colonel Custer’s battalion came closest to the encampment where 1,800 warriors of the Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapahoe Nations were gathered to protect their families. American Indian riders go bareback, leaping on and off their ponies with ease, while saddled 7th U.S. Cavalry re-enactors splash through the fast-flowing Little Bighorn River astride powerful horses.

Peak Season

Summer (the best time of year to visit is around the June 25 anniversary when a reenactment of the battle is held)

Hours

https://www.nps.gov/libi/planyourvisit/hours.htm

Fees

$25 per vehicle or America the Beautiful pass

Road Conditions

All roads are paved, including the 4.5-mile-long road to the Reno-Benteen Battlefield.

Camping

There is a small, private campground at the exit from Interstate 90, but the nearest NPS campground is 40 miles away at Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area.

Related Sites

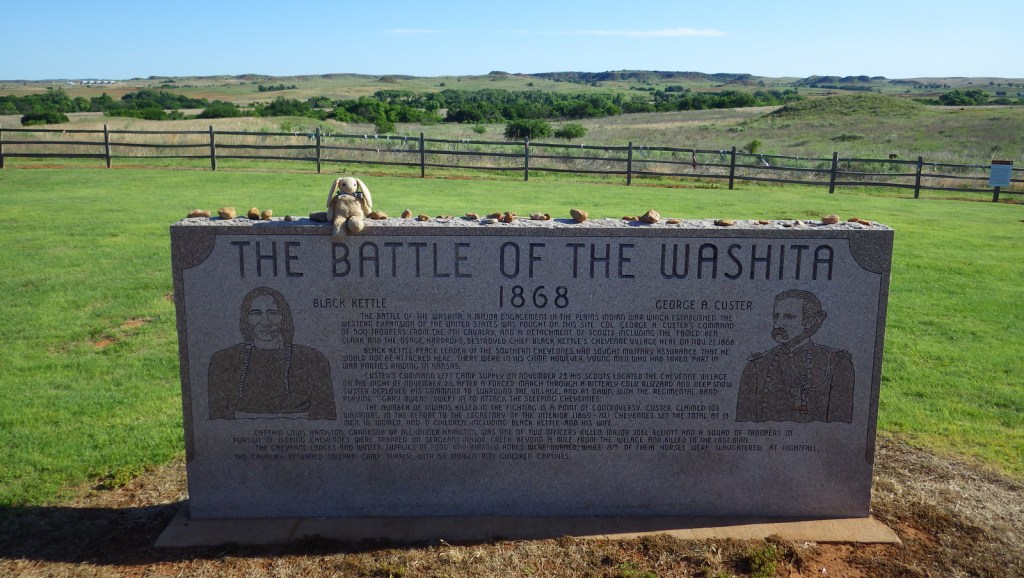

Washita Battlefield National Historic Site (Oklahoma)

Big Hole National Battlefield (Montana)

Devils Tower National Monument (Wyoming)

Nearest National Park

Explore More – When was Custer National Cemetery originally established and when did it become part of a National Monument?

Learn more about the other 137 National Monuments in our book Monumental America: Your Guide to All 138 National Monuments